Gulliver's Travels Response

A response to Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift for my English Comprehensive Program at Middlebury College in 1997.

From Part III, Chapter viii, pages 170-171:

I was chiefly disgusted with modern History. For having strictly examined all the Persons of greatest Name in the Courts of Princes for a Hundred Years past, I found how the World had been misled by prostitute Writers, to ascribe the greatest Exploits in War to Cowards, the wisest Counsel to Fools, Sincerity to Flatterers, Roman Virtue to Betrayers of their Country, Piety to Atheists, Chastity to Sodomites, Truth to Informers. How many innocent and excellent Persons had been condemned to Death or Banishment, by the practising of great Ministers upon the Corruption of Judges, and the Malice of Faction. How many Villains had been exalted to the highest Places of Trust, Power, Dignity, and Profit: How great a Share in the Motions and Events of Courts, Councils, and Senates might be challenged by Bawds, Whores, Pimps, Parasites, and Buffoons: How low an Opinion I had of human Wisdom and Integrity, when I was truly informed of the Springs and Motives of great Enterprizes and Revolutions in the World, and of the contemptible Accidents to which they owed their Success.

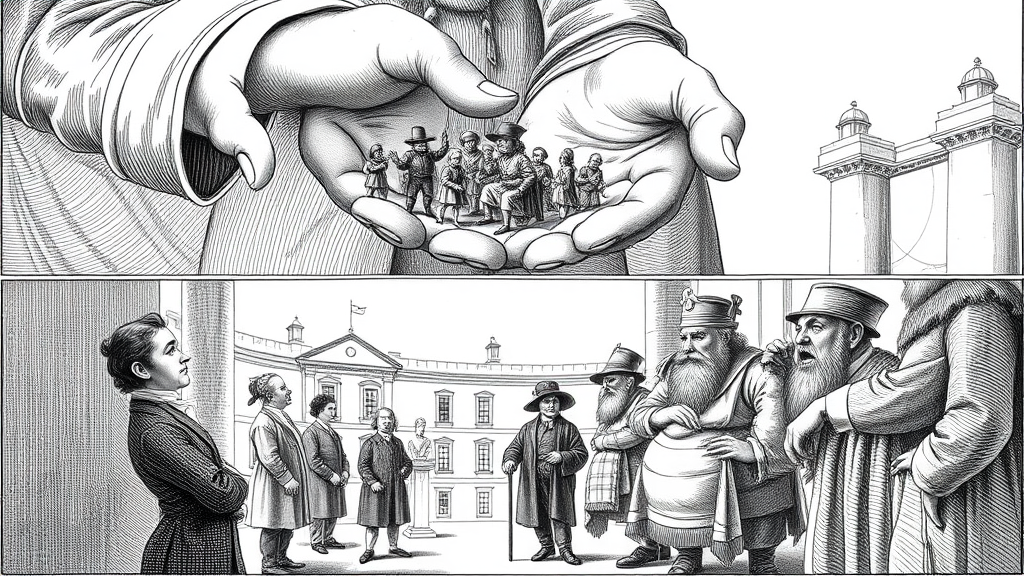

Through each travel, from Liliput to Brobdingnag, from Laputa to the land of the Houyhnhnms, as Gulliver changes scene he develops measured perspectives of the grotesque. Whether it be the magnified sight of a Brobdingnag woman’s breast or the stench of a Yahoo, Gulliver becomes privy to the grotesque nature of man through Swift’s satire. Having been able to visit with the great leaders and scholars of world history at Glubbdubdrib, Gulliver realizes the grotesque adulteration of history he has been taught and which has shaped society. It disgusts him to hear that not only has he be lied to, but that the agents of the lies are authors — or even language itself. The disenchantment with European man which Gulliver begins to experience at Glubbdubdrib grows as he discovers that he might be no better than a common Yahoo. In the ‘Voyage to the Country of the Houyhnhnms’ Gulliver manages to shift perspectives from the external to the internal: he is finally able to see the grotesque in himself.

In the first three travels, Gulliver remains a defender of English pride. It is not until he encounters the Yahoos that he becomes a misanthrope, unable to conider himself a man let alone an Englishman. However, it seems that Gulliver’s epiphany regarding the nature of humanity is not solely engendered by seeing the Yahoo in him (and wanting nothing of that relationship), but rather he has been prepped through each travel and each new society he discovers. It may be more of a gradual process than even Gulliver acknowledges. Consider the moment when connects how the Brobdingnag giants look to him with how he must have looked to the Liliputians:

I Remember when I was at Lilliput, the Complexion of those diminutive People appeared to me the fairest in the World; and talking upon this Subject with a Person of Learning there, who was an intimate Friend of mine, he said that my Face appeared much fairer and smoother when he looked on me from the Ground, than it did upon a nearer View when I took him up in my Hand, and brought him close, which he confessed was at first a very shocking Sight. He said he could discover great Holes in my Skin; that the Stumps of my Beard were ten times stronger than the Bristles of a Boar, and my Complexion made up of several Colours altogether disagreeable: Although I must beg leave to say for my self, that I am as fair as most of my Sex and Country, and very little sun-burnt by all my Travels. (71)

Even at this point, Gulliver is beginning to switch perspectives as though he will be able to point that high-powered perception onto himself and see the “disagreeable” grotesque in him. But, as yet, he cannot: he still envisions himself “as fair as most of [his] Sex and Country.” This moment together with the moment he sees the abuse of language by “prostitute Writers” reveal that Gulliver is capable of detaching body and soul and removing himself from European society.

A natural linguist, it pains Gulliver to see history abused by language that “ascribe[s] the greatest Exploits in War to Cowards, the wisest Counsel to Fools, Sincerity to Flatterers, Roman Virtue to Betrayers of their Country, Piety to Atheists, Chastity to Sodomites, Truth to Informers.” Gulliver’s own language is one that sets opposite against its opposite. He here reveals that he can vision the world from opposing points of view. This talent allows him later to pit human against Yahoo and, from their contrast and similarity, see a side of humanity to which he had been previously blinded by pride. Gulliver admires the Houyhnhnm language for its frugality and that it has no word for a lie. In revisiting history, Gulliver finds “how the World had been misled” — they have been continually told lies. It is as though everything mankind knows is wrong; we have been living a fantasy as if we were but another character in an author’s book.

Gulliver considers these abuses as “contemptible Accidents.” Ironically, accidents begin each of Gulliver’s voyages, whether they be storm, mutiny, or attack. Society itself, then, may be an accident in which the power of the few, the influence of the illuminati shape through deception. Nothing may be as in really is or was meant to be after accidental lies perpetuated a false account of existence. In denouncing accepted history, Swift seems to ask of his audience a consideration that society, government, education, human rights may be faulty. They are being asked to take a new persepctive on themselves — not be disgusted by history or to abandon it, but to be considerate of a world that can be changed. If it can be changed by writers who with a few words had Alexander die by poisoning and not of a “Fever by excessive Drinking” then Swift’s words might foster a transformation within European society (167).

Certainly, Swift uses exaggeration and comedy when he reveals how history has been altered. Then, how does one reconcile Gulliver’s distrust of writers for abusing truth with Swift’s attempts to portray Gulliver’s Travels in realistic, honest terms? That is, realistic in claiming that Laputa can be found at x minutes longitude, y minutes latitude; realistic in terms of using precise dates and so forth. The answer must rest in satire — just as Gulliver sees the absurdities in the Yahoos, Swift allows us to use our own perspective to see the grotesque in our own selves and societies through a Gulliver guide.