Examples of How AI is Used in the Classroom at Phillips Andover

Nicholas Zufelt, Instructor in Mathematics, Statistics, and Computer Science at Phillips Andover described several concrete examples of how Andover teachers are already using AI in their classrooms

Examples of How AI is Used in the Classroom at Phillips Andover

On October 8th, I attended an evening discussion in Boston featuring Phillips Academy Andover’s Head of School, Dr. Raynard S. Kington, and Computer Science instructor Nicholas Zufelt.

You can read the transcript of the discussion here.

Nicholas Zufelt described several concrete examples of how Andover teachers are already using AI in their classrooms, both in his own Computer Science courses and in other departments.

I’ve included the examples below, with some thoughts.

1. AI as a Simulation Tool (Computer Science)

Zufelt created an AI prompt that simulates himself as a teacher for students to practice oral exams. Students feed their code into AI with instructions like:

“I am a student in a computer science class. In a week, my teacher will quiz me on each line of this code. Pick a line, ask me to explain it, and give me feedback.”

This helps students rehearse conceptual understanding and practice clear explanations. It treats AI as a supporting partner, not a replacement for thinking.

Thoughts

In many ways, this approach mirrors pair programming, a common practice in professional software development where two programmers work together at one workstation — one writing code, the other reviewing, questioning, and suggesting improvements in real time. The AI acts as that “second set of eyes,” prompting students to slow down, explain choices, and identify edge cases or design trade-offs they might otherwise overlook. It fosters the same reflective dialogue that experienced developers rely on when collaborating in teams.

Beyond imitation of the teacher, the exercise also models how professional engineers learn through collaborative reasoning — articulating thought processes aloud, receiving feedback, and iterating. The goal isn’t to offload understanding to the AI but to use it as a conversational mirror, helping students become more confident communicators and more deliberate thinkers. In essence, the AI becomes a stand-in partner for the kind of peer discussion and mentorship that defines strong developer culture.

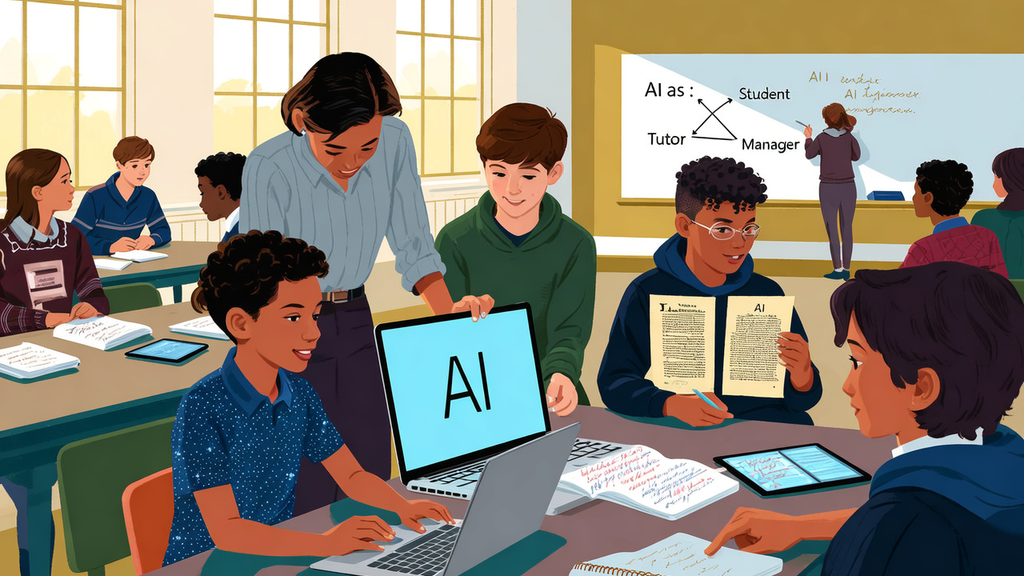

2. “AI as ____” Framework

Zufelt encourages teachers to imagine different “AI as…” use cases:

- AI as a tutor – the familiar idea of AI guiding or explaining.

- AI as a student – where the human teaches and explains concepts to the AI, reinforcing their own understanding.

- AI as a manager – simulating an employee–manager conversation to help students plan and practice interpersonal communication.

Thoughts

This framework broadens how AI can be used as a creative and reflective learning tool, emphasizing not just the what of learning but the how. Each “AI as…” scenario invites students to adopt a new perspective, shifting from passive receiver of knowledge to active participant in its construction. When students teach the AI, they externalize their reasoning; when they debate with it, they practice critical inquiry; when they collaborate with it, they rehearse professional behaviors.

What makes this framework particularly effective is its flexibility — it turns AI into a mirror for metacognition. Students can see their thinking reflected back at them, prompting deeper self-awareness about how they learn, communicate, and problem-solve. It encourages playfulness, creativity, and ownership over the learning process, reminding both students and teachers that meaningful learning often happens through dialogue — even if the partner in that dialogue happens to be an algorithm.

3. AI in History: Creating and Analyzing “Fake” Primary Sources

He highlighted Dr. Keri Lambert’s work in the History Department: After studying a real primary source, students prompt AI to generate a fake version in the same style. Then they compare the authentic and AI versions to identify inaccuracies or biases. This helps students strengthen source analysis, critical reading, and prompt design skills.

Thoughts

This activity is a practical lesson in critical thinking and source literacy. By deliberately asking the AI to imitate a primary document, students learn to treat machine-generated text as a hypothesis rather than an authority: it may sound plausible, but plausibility is not the same as accuracy. Comparing the real and fake sources trains students to look for the kinds of details historians rely on — dates, terminology, provenance, rhetorical patterns, and gaps in context — and to ask how those details support or undermine credibility.

The exercise also reinforces two technical skills that matter in the modern classroom: prompt design and evidence-based evaluation. Crafting prompts that produce different kinds of fakes helps students see how instructions shape output; analyzing the results teaches them how to corroborate claims using other sources. Importantly, it highlights the ethical dimensions of working with synthetic texts — why it matters to label created material clearly, and how easy it is for convincing errors or biases to propagate if readers suspend their judgment.

In short, the assignment pushes students to keep their own analytical muscles engaged. It’s not about rejecting AI wholesale, but about using it as a tool that surfaces questions to be answered, not answers to be accepted.

4. The “Seven-Prompt Essay”

Zufelt described a widely used writing experiment called the seven-prompt essay:

- The teacher gives a normal essay prompt.

- The student gives that to AI, receives an essay.

- The student then writes six more prompts refining and improving the AI’s output.

- The teacher grades the prompt log, not the essay.

This approach assesses editorial judgment, reflection, and metacognition — how well the student communicates with and directs AI — rather than the quality of the AI’s writing.

Thoughts

This method shifts focus from the final essay to the process of using AI as a thinking partner. Inspired by software development practices, it measures progress not just by the finished code but by the worklog output—recording steps, decisions, and iterations that demonstrate reasoning and intent. In both contexts, transparency in thinking is key.

The seven-prompt essay mirrors agentic coding principles, where students learn to effectively communicate with AI systems. By evaluating the conversation log rather than just the final essay, teachers help students develop judgment and discipline in guiding AI responsibly. This approach fosters curiosity, experimentation, and thoughtful revision—skills central to both good writing and design.

Ultimately, the seven-prompt essay reframes authorship as a collaborative process. The AI acts as a responsive instrument, amplifying student ideas when guided carefully. By focusing on the worklog output, teachers equip students with the skills needed to navigate increasingly complex AI interactions in academia and professional life.

5. “Unplugged” Assessment and Creativity

Finally, he mentioned teachers who still assign handwritten, in-class work but use it creatively: students might cut up and rearrange their written work, simulating the editing process digitally without AI tools.

This preserves hands-on critical thinking while maintaining creativity and adaptability in assessment design.

Thoughts

Paper and pencil still matter. Writing by hand slows the mind just enough to think clearly, recall deeply, and express ideas authentically. Not every task needs a screen — sometimes, stepping away from digital tools helps sharpen focus and confidence. These unplugged exercises remind students that creativity starts in the mind, not in the model.

Together, these examples show how Andover’s educators are using AI as a partner in learning — for simulation, practice, metacognition, creativity, and critical evaluation — rather than as a shortcut or substitute for thought.