Noriko and the City of the Dog: Freedom, Autonomy, and Exile

An analysis of dog symbolism in Ozu Yasujiro's Early Summer (1952), examining themes of freedom, autonomy, and exile through the film's opening sequence.

Peculiarly, Ozu Yasujiro begins Early Summer (Shokiku, 1952) with the image of a dog roaming a beach as the sea’s waves gently lap at the sand. While his opening shot lasts for approximately twenty-three seconds, the dog comprises but nine seconds, leaving the remaining fourteen seconds to a tranquil, serene shot of the sea and waves. Considering the short amount of time Ozu gives to the image of the dog, combined with the fact that the dog does not revisit the screen, the peculiarity of initiating a story concerning the process by which Noriko chooses to marry with the shot of a solitary dog encourages examination. Japanese culture’s relationship to the dog both in social and mythological terms reveals a distinct relationship of the dog to freedom, obedience, exile, abandonment, and foreign influence. Each of these themes also find sanctuary within the thematic constructs of Early Summer. By examining the symbolic function of the dog, I hope to expand on the environment in which Noriko chooses to marry.

A shot breakdown of the opening sequence offers valuable images and themes which upon analysis evokes distinct meaning to what critics of Ozu consider to be pillow or curtain shots. After the credits roll upon what appears to be a textured fabric or canvas, the film begins with the shot of the dog on the beach. All times are indexed after the credits have concluded.

| Shot# | Time | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0:00 | The sound of waves are heard. Fade in from black. |

| 1 | 0:00 - 0:09 | A small dog appears at approximately two-thirds the length of the screen from the right frame. It’s tail is up as he sniffs the sand and continues to walk off screen to the right. |

| 0:09 - 0:23 | Shot of the sea with waves landing upon the beach. Two hills form the background of the sea shot. | |

| 2 | 0:23 - 0:30 | Shot of a bird cage hanging on the outside of a house. |

| 3 | 0:30 - 0:39 | An interior shot of a house hallway with two bird cages, one at the right frame, the other center screen at the end of the hall. |

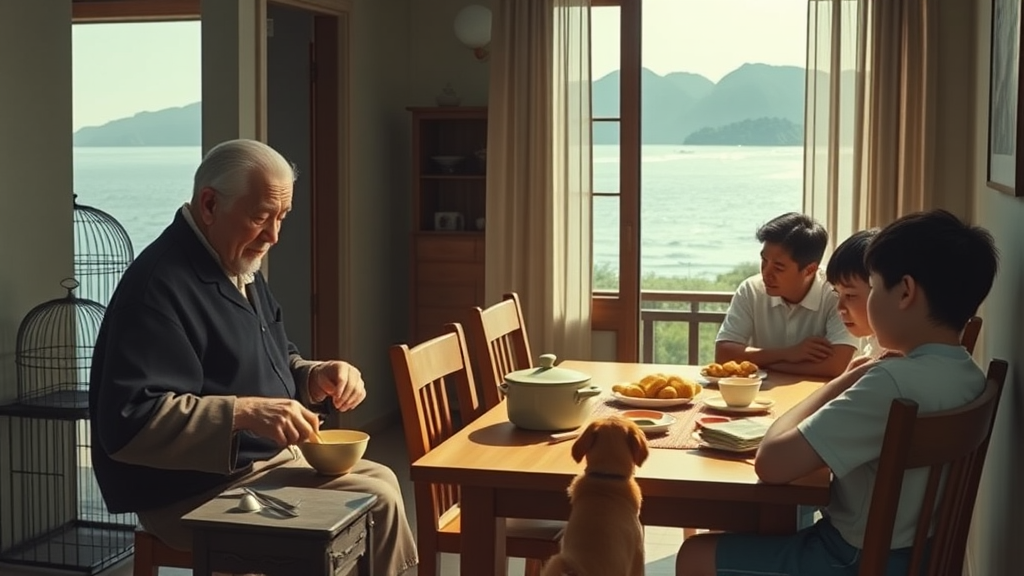

| 4 | 0:39 - 0:56 | Shot of the grandfather mixing a paste in a small bowl with a brush. |

| 5 | 0:56 - 1:12 | Medium shot of the same scene. His grandson, Minoru, enters from the left side of the screen to call him to come for breakfast. He leaves. |

| 6 | 1:12 - 1:23 | Shot of his mother in the kitchen. |

| Minoru: “I told him.” | ||

| Mother: “Put it on the table.” She hands him a bowl for the breakfast table. | ||

| 7 | 1:23 - 1:39 | Shot of the table. Noriko centers the shot and faces the camera. Minoru sits down. |

| Noriko: “Here are some pickles. Isamu up” | ||

| The brother calls out for Isamu to come to the table. | ||

| 8 | 1:39 - 1:47 | Isamu comes out of his room, entering a hallway, and pulls up his trousers. Looks grim or tired. |

| 9 | 1:47 - 1:59 | He sits at the table to join his brother and aunt. |

| Noriko: “Did you wash your face?” | ||

| Isamu gets up. | ||

| 10 | 1:59 - 2:06 | Same shot position as #7. The mother is still in the kitchen and looks up as Isamu enters the hall. |

| 11 | 2:06 - 2:24 | Shot of laundry room; a wash basin is located at the left and a sink in the background. |

| Isamu walks into the laundry room, takes a towel from a shelf at the left of the screen, walks to the sink, wets it, then puts it back on the shelf, without washing his face. | ||

| 12 | 2:24 - 2:39 | Shot of Noriko and brother at table eating. Father, Koichi, is in background putting on his coat, readying for work. Isamu enters from the back left of the shot and sits down opposite Noriko with his back to the camera. |

| Noriko: “Did you wash your face already?“ | ||

| 13 | 2:39 - 2:44 | Centered close up of Isamu. |

| Isamu: “I did. The towel’s wet go and see.” | ||

| 14 | 2:44 - 2:49 | Close up of Noriko. She smiles and gives Isamu a bowl of rice. |

| 15 | 2:49 - 3:08 | A shot of the three at the table eating. Koichi is still getting ready for work. Grandfather enters the shot from the foreground left. He puts his hand atop Isamu’s head. He asks Noriko to mail a letter, “Will you mail it?”, and sits down opposite brother, next to Noriko. He tells Isamu to “Chew well.” |

The first three shots of Early Summer are absent of human form, focus on an aspect of nature and set a peaceful mood to the beginning of the film. Critics consider these three shots to be pillow or curtain shots, a characteristic distinctive of Ozu’s style. However, there appears to be a method in the ordering of these four images (dog, sea, bird cage, house). The transition from one image to the next suggests a symbolic meaning that may be revealed when one examines how each image functions within the film and within Japanese culture.

I suggest that the transition from dog to bird cage to the house comments on the theme of freedom in Early Summer. Noriko, initially having had a husband chosen for her, exerts her freedom of choice and decides to marry her childhood friend Yabe Kenkichi against the wishes of her family. Having already been assigned to practice medicine in a hospital in Akita, Kenkichi and Noriko must leave Tokyo and the family. Her departure splits up the family. Freedom to chose her own husband, a Western ideal, goes against a long-standing Japanese tradition of arranged marriage. Noriko disobeys her family. Indirectly, yet importantly, a result of her disobedience is a form of exile.

In Western culture, a dog is considered to be obedient to its master, subservient to its master, and domesticated. However, in Japanese culture, the dog is considered in a decidedly different manner. Suzuki Takao claims that a dog is a free and autonomous being.

Man and dog, though fundamentally independent of each other, simply happen to cross paths. Until recently there was no custom in Japan of keeping dogs leashed or fenced in. Dogs used to walk around freely, looking for garbage or discarded food.

There exists a custom in Japan to abandon unwanted dogs. Suzuki points out that in England, if a dog is unwanted, its owner usually has the animal killed. He notes that, “When a Japanese abandons unwanted puppies, his sole purpose is to put them as far away as possible from the sphere of his daily life in order to sever unnecessary ties.” Thus, from the first shot of the film, notions of freedom, autonomy, and abandonment have been established.

The next image is that of the bird cage. In this image we find the representation of captivity. Caged, the image of the bird opposes the freedom of the dog. The dog has the ability to exit the screen; he leaves the boundaries of the frame. However, the bird is trapped inside the cage. His food is given to him by the grandfather (he at one point in the film mentions that he is going out to buy its food) and is completely dependent on its human master. It has no autonomy and leads a confined life. In space we have moved from the seashore to the very outside walls of a house.

Next we move to the image of two bird cages inside the house. This transition carries the theme of captivity from an external force to one that lives together with the family inside. Like the bird cage, the house seems like a cage. Yet, there seems to be a will to disobey and break from the cage. The foundation for disobedience is laid in the initial sequence by Isamu pretending to wash his face. Noriko, I suggest, hopes to counter the confines of Japanese tradition, familial obedience, by attaining the freedom of the dog.

In Chinese mythology, the symbol of the dog stands at the gate between barbarism and utopia. The dog often represent the barbaric invaders of the north. A dog was also a figure to be exiled, in the case on the cynocephelic werewolf. In Japanese mythology the dog is not a malicious animal, such as a serpent, it often aided mothers in childbirth and was a obedient, yet independent, companion of such mythic heroes like Momotaro (The Peach Boy) or Tametomo. The legend of Tametomo and his Dog provides an interesting insight into the penalties for disobedience. The youthful Tametomo was once ordered by his family to live in another province with another family for normal parental discipline would not work on him. His faithful dog accompanied him on the journey and on the way, they rested underneath a pine tree. Tametomo’s dog leap up, frenziedly, and began to bark. In a fit, Tametomo drew his sword and beheaded his dog. Yet, instead of falling over dead, the dog’s disembodied head flew up into the tree and killed a dangerous snake. With the snake in its jaws, the dog’s head came crashing down. Tametomo felt guilty about killing his dog and later buried it in a carefully dig grave, grateful for his dog’s faithful service. Although the dog was in fact protecting his master, his disobedience at barking met with the penalty of death.

Punishment for disobedience is death or exile in Chinese and Japanese mythology. In the same way that Noriko disobeys her family wishes for an arranged marriage, she, too, is exiled. It is either interesting or ironic to note that Noriko is to be exiled to Akita. Akita, noted by her family members as distant, cold, and foreboding, is also a breed of dog — the Akita inu — developed in Japan during the Edo period as a fighting dog to entertain the local daimyo. The Japanese word for dog, inu, is also associated with an outcast minority people, the Ainu, who live in the northern regions of Hokkaido. Therefore, the symbol of the dog, to the Japanese, may very well contain not only the sense of freedom and autonomy, but also of exile, barbarism, and the outcast.

For Noriko’s family, her exertion of individual choice in whom she will marry is a Western display. Therefore, in the opening shot of the dog upon the beach, it is standing between sea and land — or, perhaps, between the Occidental and the Japanese. The symbolic image of the dog also evokes the problems obedience to ones master or, in Noriko’s case her family, creates. As the dog stands between Japanese and Occidental, the dog also stands between subservience and autonomy. These are ideals Noriko faces when deciding whom to marry. If she marries the chosen husband, she is serving her family wishes. If she chooses on her own, she is expressing her autonomy. Yet, as we have seen, this autonomy has its punishment. For Noriko, that punishment is exile to Akita, the city of the dog.

References

- Suzuki, Takao, “Words In Context: A Japanese Perspective on Language and Culture” (Tokyo: Kodansha Ltd., 1978), 101.

- White, David Gordon, “Myths of the Dog-Man” (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), 161-177.

- Piggott, Juliet, “Japanese Mythology” (New York: Peter Bedrick Books, 1982), 89, 92, 116.

- Kodansha Encyclopedia (Tokyo: Kodansha Ltd., 1983) Volume 2, 124-125.